Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday, 26 August 2017 00:37 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

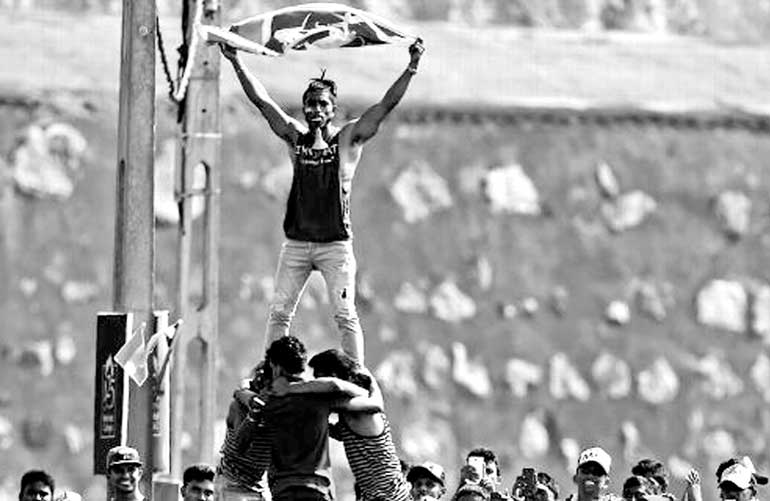

Pyramid pose: the problems of Sri Lankan cricket start right at the top - AFP/Getty Images

ESPNCricinfo: In the end, what stays with you the longest from cricket in Sri Lanka is the crows. The papare band can fade away, Galle Fort can seem run-of-the-mill after a while, Percy can sometimes grate, you can get away from the shouts of “Aluwa aluwa”, but the crows stay with you long after you have gone.

They are looking for worms in the warm, moist grass while cricket is on, but they could easily be doing what crows do: Wait to feast on carcasses; in this case, those of the opposition after the home team is done with them.

The crows always seem to sneak up on you in Sri Lanka. And so does Test cricket. Tests here just start. You wake up, have your pol roti and chilli-onion sambal at the National Tea Room in the fort, or in one of the tea rooms near the station outside, and walk in to watch the highest form of cricket (so they say) for free. If you are on a motorbike, you don’t even need to remove your helmet. Just stand outside the fence and watch.

There is a personal, informal touch to the relationship between the fan and the cricket – and indeed, the fan and the cricketers – that should be the envy of all cricket nations.

When the team is not doing well, the fans resort to satire – at the grounds or on social media – and not protests of the kind their neighbours partake in.

In the days before the start of a Test, there is no build-up, no player talking about the other team’s weakness, not even the sort of overbearing security at the grounds that makes you feel unwelcome – a sure sign of an important event in Asia.

They don’t scream from the rooftops that some of the best Test cricket this side of 2000 has been played in Sri Lanka.

It starts with the pitches. P Sara seams and later turns. Galle dries faster than quick cement. SSC, an old culprit, turns for the first hour, then settles down before becoming a turner again. In the hill country, there is always some help for the quicks.

The last 19 Tests here have produced results. Since 2000, 350-plus scores have been successfully chased three times, and targets of under 200 have been successfully defended on three other occasions.

Sri Lanka have won 47 and lost 24 Tests at home since 2000, but they have done it without templates. They have a habit of finding unassuming and unexpected heroes. They do things subtly.

Here, the ball doesn’t thud into the keeper’s gloves, his head high and pointing skywards. The seam movement or the turn or the bounce are rarely exaggerated, but they are always enough to keep the batsmen honest. In the five years before the recent series against India, Sri Lanka was the toughest place in which to open a Test innings.

The Sri Lankan team have managed to find ways to get on a roll. When they do so, it is not like India, where it is an all-encompassing, all-consuming force, where the opposition can feel like a deer stuck in an Indian traffic jam with vehicles surrounding it and honking loudly. Sri Lanka don’t snarl at you; they don’t seek to leave psychological imprints on your next generation the way the Aussies do.

The light is fading and darkness is engulfing Sri Lankan cricket - PA Photos

The light is fading and darkness is engulfing Sri Lankan cricket - PA Photos

But everything goes right. Short leg and silly point catch everything. Deep midwicket becomes a catching man placed in the exact square foot where your release shot lands. There is no sledging, no send-offs. Just a cackle. Sri Lankan fielders laughing and speaking a language foreign to the rest of the cricket world. Are they laughing at you? Are they laughing among themselves? Do you even matter?

Beating Sri Lanka in Sri Lanka has rightly been an achievement without which a Test team can’t be assumed to be great. Their spinners know what pace to bowl on these slow turners, how exactly to use the ever-changing breeze. Their batsmen know how to conserve energy in the sapping humidity and play long innings. Their captains know how to read the pitches, which can be dangerously misleading.

One of Sri Lanka’s favourite sides to beat has been India. They knocked them out of the 2007 World Cup, and out of the World T20s of 2010 and 2014. Perhaps because they see how the administration kowtows to the BCCI, it is almost as if the Sri Lankan people’s pride is on the line every time they play India.

The Bollywood song “Dekha Hai Pehli Baar”, from the early-1990s movie Sajan, is quite popular in Sri Lanka. Not a Sinhalese adaptation of it but the original Hindi song. You can’t walk through areas around a train station or a bus stop without hearing it. It plays even at the grounds. Ask Sri Lankans how they know the Hindi lyrics and you are likely to be told there was too much idle time to spend during the 952 Test.

Now, though, India have won their last five Tests in Sri Lanka, the last three in a total of 11 days. The middle one among these three came during the 20-year anniversary of the 952 Test. It took Sri Lanka five innings to score 952 runs against India in this series.

The main architect of that 952, Sanath Jayasuriya, is the chief selector now. He spends hours standing next to the pitch on the day before a Test. Unless he is willing the pitch to change its nature through fierce concentration, he basically instructs the groundsmen to give him what he wants. Hashan Tillakaratne, long-time team-mate of Jayasuriya, is the batting coach. When he was a national selector two years ago, his twins made it to the Sri Lanka Under-19 side. Before that Tillakaratne was known for making fixing allegations against Sri Lankan cricket.

Apart from head coach, Nic Pothas, the entire coaching staff is comprised of former Test players, all of whom used to be team-mates of each other. But Lahiru Kumara’s school coach is the one to point out that the fast bowler keeps getting his feet tangled up as he enters his delivery stride.

Pothas himself said he was not disappointed in his side’s performance during the second Test, exhibiting the kind of artificial optimism SLC’s press releases are ridiculed for. When he did suggest that outside interference was getting to him, he had to immediately turn up for a press conference to say he was very happy with the board.

Just like with Kumar Sangakkara and Mahela Jayawardene, there exists no succession plan for when Rangana Herath leaves.

Kusal Mendis and Dhananjaya de Silva came up almost by accident, a tribute to the still robust schools cricket system, and helped Sri Lanka win the series against Australia. But since then they have not been handled well.

When India’s ODI squad for the tour of Sri Lanka was announced, it emerged the selectors had identified a core group of 26 players for the next World Cup, all good limited-overs players. Add the five or so Test specialists and you know India have a core group of more than 30 players. Sri Lanka don’t have a replacement for Upul Tharanga, who averages 32 in Tests and even captains them in ODIs. Chamara Kapugedera is still a thing despite an average of 21 as a specialist batsman in ODIs.

On the field, the subtlety, the challenges, are all but gone. Just like they do for the holidaying tourists, Sri Lanka today are doing their best to make the stay of cricketing teams enjoyable.

Captains are clueless, bowlers lack experience and discipline. Batsmen don’t know what to do once you cut their boundary options. That feel for the game that Sri Lanka had at home is disappearing. Plans are so rigid it seems the captain is awaiting ratification from the sports ministry before they can be changed.

July 25, when hopes for a competitive series were pinned on Herath’s 39-year-old fingers, now seems like an age ago.

Since then the free view from outside Galle stadium has been blocked. During that first Test, even the magnificent fort began to look like an eyesore, because it came with the painful sight of Sri Lanka’s inability to put up a fight. Percy swears he will come to Sri Lanka matches as long as he can walk – “even in a wheelchair” – but people are either leaving or have left. They are now giving up on satire and instead surround team buses. The papare band turned up once but couldn’t be bothered to compete with the stadium DJ between overs. If the musicians played through the overs, as they have done for decades before, the umpires ask them to stop. So the band has also left.

Only the crows remain. Waiting. For a carcass.