Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Monday, 4 November 2024 00:07 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Revenues from tourism, rather than being invested in new industries, tend to perpetuate a speculative cycle of underdevelopment

On 23 October, the United States embassy in Sri Lanka issued a travel advisory warning of a potential attack targeting tourist sites in Arugam Bay, a popular surfing destination in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka. The embassies of the United Kingdom and Russia soon followed suit. Given the mysterious circumstances of the 2019 Easter attacks that occurred following a warning by Indian intelligence services, this has understandably stirred much anxiety and speculation among Sri Lankans.

On 23 October, the United States embassy in Sri Lanka issued a travel advisory warning of a potential attack targeting tourist sites in Arugam Bay, a popular surfing destination in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka. The embassies of the United Kingdom and Russia soon followed suit. Given the mysterious circumstances of the 2019 Easter attacks that occurred following a warning by Indian intelligence services, this has understandably stirred much anxiety and speculation among Sri Lankans.

What the recent travel advisories did not mention is the operation of illegal businesses by Israeli tourists in the Arugam Bay area, and the opening of Jewish places of worship in close proximity to local Muslim mosques. To make matters worse, it is reported that many of these tourists are possibly IDF soldiers engaging in the proliferation of Zionist propaganda.

While there is much to be said about these developments, there is also an opportunity here to discuss the more general shortcomings of tourism as an economic sector and Sri Lanka’s toxic dependence on it.

Integrated development

In a 1975 essay on class contradiction in Tanzania, the Guyanese historian and political activist Walter Rodney wrote about how university students in the newly independent United Republic of Tanzania debated the place of tourism in economic development. Rodney summarised the views of the opposing camp thus:

“They were saying that our workers and our peasants are not concerned with those who want to come and watch the lions and gazelle and to watch the Masai and so on, and call themselves tourists: that this will not do anything for the mass of our population. On the contrary it will inhibit a development of serious economic options which could lead to real integrated development.”

Rodney’s use of the words “integrated development” is key. Tourism is at best a stop-gap measure in conditions of serious economic and technical backwardness to raise foreign currency. The barriers to entry in tourism, in terms of skills and technology, are fairly low. While tourism can raise revenue, it historically has been incapable of re-investing resources into more dynamic economic activities.

Like agriculture, tourism is subject to diminishing returns. It is a classic rentier activity dependent on natural endowments like land and its proximity to ‘attractions’. The scope for value-addition in tourism is also fairly low. Tourism lacks the economies of scale, division of labour, and capital deepening that are characteristic of manufacturing and large-scale industry. At best, it may help augment the home market for domestically produced goods. However, this in turn requires activist policies to improve local content.

Like agriculture, tourism is subject to diminishing returns. It is a classic rentier activity dependent on natural endowments like land and its proximity to ‘attractions’. The scope for value-addition in tourism is also fairly low. Tourism lacks the economies of scale, division of labour, and capital deepening that are characteristic of manufacturing and large-scale industry. At best, it may help augment the home market for domestically produced goods. However, this in turn requires activist policies to improve local content.

The lobbies and interest groups surrounding the tourism sector have congealed to such an extent that it seems impossible to have a productive conversation on the place of tourism in a national development strategy. A whole public-private institutional nexus exists to support the tourism sector. Every political party, left or right, must pay heed to the sector.

There is a case to be made that Sri Lanka’s overreliance on tourism diverts productive resources such as land, labour, and even state capacity (if we wish to view it as a precious resource) away from productive economic activities that could have a more long-term impact on developing the country. Revenues from tourism, rather than being invested in new industries, tend to perpetuate a speculative cycle of underdevelopment.

The missed wake-up call

The pandemic should have been a wake-up to Sri Lankan policymakers that non-tradable services such as tourism, are no foundation on which to build a modern economy. It is instructive that the economies of our regional competitors in tourism, such as Vietnam, Malaysia, and Thailand, did not collapse the same way Sri Lanka did during the pandemic. This is because they are rising manufacturing powers first and tourist attractions a distant second or third.

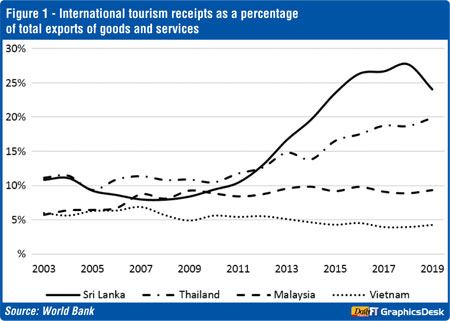

One measure of dependence on tourism is the share of international tourism receipts in exports. In 2019, on the eve of the pandemic, tourism receipts accounted for nearly a quarter of Sri Lanka’s exports (24%). By contrast, the figure was 20% for Thailand, 9.3% for Malaysia, and only 4.2% for Vietnam. While the Sri Lankan economy imploded during the pandemic, Vietnam boomed, as its dynamic industrial sector was able to adapt to shifts in global demand for manufactured goods. Vietnam was also agriculturally self-sufficient enough to feed its own population.

Aside from the economic case to be made against tourism as a core component of development strategy, there are also social and cultural arguments that warrant consideration. Is tourism a dignified way to rebuild a country after the ravages of 500 years of colonialism? Should we not have the clear-eyed and sober goal of developing our productive and technological capabilities so that our people can partake in world trade as equals, and not just beggars and debtors?

I am reminded of a quote by the freedom fighter Philip Gunawardena, who said that the need to industrialise was not simply to attain power but to get rid of poverty, improve living standards, “and to give our people, when they are free from the pursuit of inadequate food and shameful housing, the leisure and serenity to enjoy our beautiful country; to develop their culture in their own way.”

Our collective dependence on tourism amounts to a perverse inversion of this dream. Foreigners enjoy our beautiful country, and our culture debases itself in order to entertain them. Yet the majority of our people remain in poverty and in search of food, housing, and, most shamefully, better countries in which to raise their children.

(The writer is a researcher at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He holds an MSc in Economic Policy from SOAS University of London. He can be reached at [email protected].)