Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Friday, 11 June 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

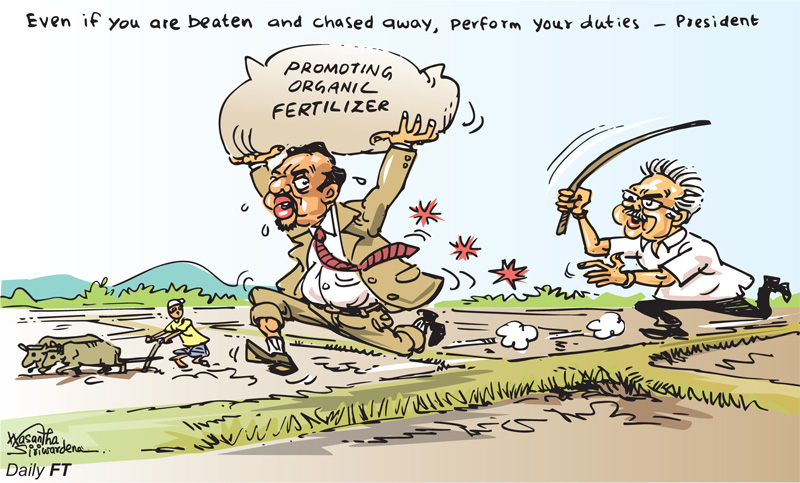

Had not the Government imposed a ban on the use of chemical fertiliser and agro-chemicals, agriculture should have been a major sector for the Government’s attention in its effort to overcome the looming threat of being a failed state.

Had not the Government imposed a ban on the use of chemical fertiliser and agro-chemicals, agriculture should have been a major sector for the Government’s attention in its effort to overcome the looming threat of being a failed state.

An integrated approach that gives priority to agriculture could have helped the nation to ensure food security whilst at the same time creating an environment conducive to providing a safety net for those retrenched from other sectors due to the current economic slowdown.

Like in everything else, the country’s agricultural sector is in complete disarray. The present situation should have been used as a supreme opportunity to unravel the chaos created by the crisis and to put the agricultural sector on proper rails and correct path.

A movement of Farmers’ Co-Operative Societies

Here I have included a wide range of activities: paddy cultivation, field crops, commercial estate plantations, fisheries, livestock and forestry in the definition of agriculture. Although 25% of the labour force is engaged in agriculture, its contribution to gross national product is only 7%.

Not only the conventional agriculture based on food crops including paddy cultivation, but also the commercial agriculture based on household plantations remains at a level of stagnation. It is only a meagre income of Rs. 40,000 per acre per season that a farmer can earn from paddy cultivation. The wages of the workers employed in the commercial estates is around Rs. 1,000 per day. The rulers of Sri Lanka are still tending to follow the example of King Parakramabahu in farming and agriculture.

Taking into account the epidemic situation and the hardships encountered by the farmer community, it would be possible to set up Farmers’ Cooperative Societies in agricultural areas in Grama Niladhari divisions and establish a strong and modern Farmers’ Co-operative Society movement which could be turned into an expansive institutional system to buy the produce of the farmers who have been rendered miserable due to being unable to sell their produce and sell them to the consumers at a reasonable price, most of whom are in dire straits at the moment.

By doing so, it could be developed into a well-organised Farmers’ Cooperative Society Movement, winning confidence of both the farmers and the general public during the pandemic period itself.

The problem of wild animals

Initiation of appropriate action to minimise the immense damage caused to agriculture by wild animals can be considered as an indispensable condition for the development of agriculture in Sri Lanka. The damage caused to agriculture by wild animals remained close to 40% according to an estimate published during the regime of President Maithripala Sirisena.

While the Government’s decision on the use of chemical fertiliser is not correct, the decision to issue guns to farmers to control the damage done to agriculture by wild animals is correct. A country should have a policy to control the population of wild animals that harms agriculture. No country will allow a big increase in the density of the population of wildlife that would cause great damage to agriculture.

Prior to the insurrection in 1971, it was the farmers who controlled the population density of wild animals that harmed agriculture. During the ’71 insurrection, the right of the farmers to possess guns was withdrawn. There has been a rapid growth of the density of population of wild animals as the governments that came to power since then and up to now have given priority to the protection of wildlife rather than that of the farmers.

The density of population of rilavs and monkeys is so thick that a substantial portion of them have to be destroyed to bring the level of damage caused by them to a bare minimum. Perhaps it may be possible to sell the excess animals to countries where there is a demand for their meat.

As it would not be affordable for the farmers to purchase guns at market prices, a system could be introduced to lease guns to farmers of the agricultural regions, for a short period of time (for a fixed number of days) and sell only the ammunition under the supervision of the Grama Niladharis. It is also possible to create a system where a portion of the income earned is given to the Grama Niladharis who fulfil this responsibility.

The growth that can be secured in the yield of coconut alone would be very large if the density of population of rilavs and monkeys is controlled.

Milk and meat

Sri Lanka spends $ 1.6 billion on food imports. The agricultural sector can be transformed into an important segment of the economy with a dynamic force which could generate huge incomes, provide a greater source of livelihood for a large portion of labour force and contribute a significant share to the national income by producing certain imported food items and also cultivating certain items that could be substituted to the imported items locally, on a pragmatic plan.

But for that, the rulers of Sri Lanka must have the courage to abandon the stupid and irrational ideas and beliefs that they are engrossed with in the name of religion or culture. Sri Lanka can easily become self-sufficient in milk if it is possible to get rid of the foolish and stupid ideas held in regard to the production of beef.

Cattle farming based on the production of milk only without meat cannot be economically viable. Although Sri Lanka has failed to understand this simple truth, it is not difficult to understand it. Anagarika Dharmapala scornfully referred to those who consumed beef as “outcasts who eat geri mas (beef)”. In India the Hindus worship the bull as a god. Therefore, India is considered as a country having a large population of cattle, and the majority of people do not consume beef. But India is the world’s largest exporter of beef.

Sri Lanka could easily become self-sufficient in milk industry provided it is prepared to abandon the stupid policy adopted with regard to the production of beef, and apply the progressive policy it has adopted in regard to the poultry industry. Such a policy will invariably make cattle farming in Sri Lanka a profitable industry and will enable dairy farmers to earn higher income.

Dhal, chilies and potatoes

The preference of Sri Lankans for dhal is huge. In folklore, dhal is equated to love and life without love is compared to a hotel without dhal. The annual cost of importing dhal amounts to $ 79 million. Dhal is considered to be a crop that cannot be grown in Sri Lanka. Yet, Kusal Perera, in a note written by him, has stated that dhal (lentils) have been cultivated in Vakarai, Jaffna successfully and the harvest is being reaped now.

Whatever may be the potential to grow dhal in Sri Lanka, it has long been discovered that the split green gram can be used as a good substitute for dhal. But split green gram is no longer available in the market. If green gram could be substituted for dhal, it will certainly lead to a great improvement in the cultivation of green gram in Sri Lanka.

Sri Lanka produces only about 15% of the requirement of dried chillies. The rest is imported. The annual import cost of dried chillies amounts to Rs. 10,542 million. The income that can be earned from an acre of chillies is 10 times more than the income that can be earned from an acre of paddy. A national effort to become self-sufficient in dried chillies will help not only to save a large amount of foreign exchange, but also lead to create a rich peasantry as well. Of its potato requirements, Sri Lanka produces only about 35%. The import cost of potatoes is Rs. 11,619 million.

In this way, producing imported foodstuffs which could be cultivated in Sri Lanka alone will enable the country to make a significant improvement in the traditional agriculture and at the same time transform it into a viable sector capable of providing protection for those who have been retrenched from other sectors.

Paddy cultivation

In adopting a realistic vision for a major improvement in traditional agriculture, it is important that we re-examine the enormous priority given to paddy cultivation. Paddy is a crop that has shown great progress in terms of yield. The growth in paddy harvest from 1952-2018 has been as high as 700%. Although this growth has made the country self-sufficient in rice, it has not contributed to enrich the paddy farmer.

My opinion is that the paddy cultivation is a source that cultivates poverty for the farmer. The farmer, if he is lucky, can earn only Rs. 40,000 per acre per season from paddy cultivation. On the contrary, it would be possible to earn 10 times more (Rs. 417,000) from cultivating chillies, six times more (Rs. 246,716) from cultivating potatoes, eight times more (Rs. 319,696) from cultivating tomatoes, nine times more from cultivating carrot (Rs. 384,099) and six times more (Rs. 264,578) from cultivating eggplant or brinjal.

Sri Lanka has set aside an extent of land for paddy cultivation, may be due to the fact that rice being the staple food of the people. The total area allocated is 922,151 hectares or 14.06% of the total land area of Sri Lanka. It again represents 44.23% of the land allocated for all crops including commercial cultivations (208,499 hectares). It has long been my opinion that the cultivation of paddy in the wet zone was not economically viable and that the entire requirement of rice of Sri Lanka could be produced in the dry zone, which is now being accepted by agronomists also.

It would be possible to restrict paddy cultivation only to the dry zone by discouraging it in the wet zone. The country has a greater potential to produce all the rice it needs in the dry zone. Since the income that can be earned from paddy cultivation is at a very low level, a system can be introduced to provide a special subsidy to paddy farmers in the dry zone. By doing so, about 400,000 acres of land used for paddy cultivation in the wet zone can be utilised for cultivation of other crops which are economically more viable and for the use of the other activities as well.

As in the case of many other things, the way Sri Lanka perceives agriculture is exceedingly backward. In agriculture and irrigation, we still follow the example of King Parakramabahu. How big is the immense wealth spent on irrigation schemes initiated emulating the King Parakramabahu?

We hoped that the giant Mahaweli scheme would herald a rich and modern generation of farmers. We anticipated becoming self-sufficient in electricity and selling the surplus to India and earning a large income. If all these investments had been made for promoting modern agriculture, the result would have been more fruitful.

One of the main reasons for our failure seems to be our lack of interest in attempting to do innovative things and adherence to doing only familiar things we were used to doing. We do not produce food items that others consume and could be sold to them, except for producing things that we ourselves eat.

Since 1948 Kalutara District has shown a consistent loss from paddy cultivation, every year. More than 70 years has lapsed now; yet, the lesson to be learnt from this trend has not been realised. The inability to see things sharply and critically can be considered an inherent feature of Sri Lankan agriculture. The use of agricultural land in Sri Lanka is incredibly poor.

The kitchen of an average household in Sri Lanka is relatively outdated and backward. The food pattern is monotonous and devoid of much variety. The number of food items consumed are limited and the recipes used for cooking are restricted to a few dishes: with gravy, no gravy or fried with oil, etc. Often, the same things are eaten almost every day, prepared in a few limited ways. So the one who cooks the food and those eating them do it mechanically, and not with pleasure.

The people in Sri Lanka are used to eating a large plate of rice served in the shape of a dagoba with some curry and a vegetable. Meat is rarely eaten. They know only one or two methods of cooking cabbage. Their knowledge in the proper preparation of tomato is almost nil. There is hardly any change in conventional culinary practices, and new innovative methods of cooking are rarely adopted.

The per capita meat consumption in Sri Lanka is 6.3 kg. In Myanmar and Vietnam, both can be considered as Buddhist countries, the per capita meat consumption is 32.8 kg and 48.9 kg respectively. It is 111.5 kg in Australia. Like Japan, Sri Lanka too should become a country that consumes less rice and more meat, fish, vegetables and fruits. Such changes in food consumption patterns affect everything else in the country.

Unless the ban on chemical fertiliser and agrochemicals is lifted, it will inevitably sound the death knell of Sri Lanka’s agriculture. Agriculture, devoid of chemical fertiliser and agrochemicals, and solely depending on carbonic fertiliser, can be considered a striking dream, yet unachievable. Bhutan is an ideal example for such utopian approaches.