Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Monday, 15 July 2024 00:45 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The longer the Bank keeps mum on the sources of funds for awarding the high interest rate in 2023, the higher the speculation that there was some accounting window dressing

Aseni, the whiz kid in economics, and her grandfather, Sarath Mahaththaya, a former official of the Ministry of Finance, have been in very intense interactive discussion of the debt and debt restructuring problem of Sri Lanka. In the previous episode, available at: https://www.ft.lk/columns/A-child-s-guide-to-debt-and-restructuring-Country-driven-to-economic-collapse-has-not-many-options-Part-I/4-763940, they discussed why only bilateral and commercial borrowings of Sri Lanka have been earmarked for restructuring when the country’s total foreign debt had been a massive amount.

The multilateral debt from the IMF, World Bank, and ADB, etc., had been excluded from the debt suspension because of the risk of being blacklisted and ineligible to draw on them to get out of the country’s debt crisis. It was also noted that the foreign reserves are being overstated by the Central Bank giving a misleading message to the politicians, and the members of the public by including the unusable SWAP facility from the People’s Bank of China amounting to Chinese Yuan 10 billion, approximately about $ 1.4 billion, in the reserves. It was also found that, in terms of the assessing reserve adequacy or ARA metric of the IMF, the country’s reserves standing at 40% of the required amount were inadequate. They have continued the interactive conversation.

Aseni: Grandpa, by quoting the Central Bank figures, you said that the country’s total foreign debt at end-2023 amounted to $ 55 billion. I went through the relevant table in the new Central Bank annual report and found that it had reported the debt on account of the issue of international sovereign bonds, also known as ISBs, had been reported at the market value of those bonds at $ 5.5 billion, whereas the total liability of Sri Lanka on this count had been $ 12.55 billion. What is the logic of this underreporting? What should be the actual foreign debt liability of Sri Lanka?

Aseni: Grandpa, by quoting the Central Bank figures, you said that the country’s total foreign debt at end-2023 amounted to $ 55 billion. I went through the relevant table in the new Central Bank annual report and found that it had reported the debt on account of the issue of international sovereign bonds, also known as ISBs, had been reported at the market value of those bonds at $ 5.5 billion, whereas the total liability of Sri Lanka on this count had been $ 12.55 billion. What is the logic of this underreporting? What should be the actual foreign debt liability of Sri Lanka?

Sarath: Sorry, I also missed that point. There is no economic logic in doing so. In terms of the principles of finance you have learned, a creditor can report the value of loans he has granted at the market price because that is the amount which he can get from his borrowers. That is known as the marking to the market value. It is a loss to the creditor and that loss is charged to the profits and loss account. But doing the same by a borrower has no meaning because, irrespective of the market price, he should repay the principal amount. It seems that the Central Bank has confused the borrower with the creditor. Sri Lanka is entitled to mark them at the market price if the lenders, in this case those who have invested in the ISBs, have agreed to forego that amount of the reduction of the principal value. That is known as a haircut in the normal finance terminology. If it happens, that is a gain for Sri Lanka and that gain should be added to the Government revenue as a profit since macroeconomic accounts, the fiscal sector, external sector, monetary sector, and national accounts, are all recorded by using double-entry bookkeeping principles.

If you debit one account here, you should credit another account. In this case, when the debt account is debited, the Government revenue account should be credited. Without going by this procedure because we do not see the counter entry in the budget, the Central Bank has simply recorded the value of ISBs at the market price. It has therefore underestimated the ISB liability by $ 7 billion and when that is added to the total country debt it amounted to $ 62 billion or 74% of GDP.

The average market value of the ISBs at end-June 2024 amounted to $ 59 for a bond of $ 100. That was a discount of 41%. In common parlance today, that is the haircut which Sri Lanka should get when it reaches agreement with ISB holders for restructuring the same.

Aseni: That is now clear. What about the domestic debt? Was it also a part of the original restructuring plan?

Sarath: Sri Lanka did not or does not have a problem about repaying its domestic debt though the debt level is high and is rising at a high rate. That is because, given the country’s interest rate structure and ability to change the interest rates, the Government can repay its domestic debt by further borrowing which we call ‘debt refinancing’. Even though the Government cannot borrow from the Central Bank to repay its debt in terms of the prohibitions in the new Central Bank Act, it can borrow from the market or from commercial banks. Borrowing from the latter amounts to money printing because it will increase the total money stock. This was what the Government had been doing since the suspension of the servicing of bilateral and commercial debt in April 2022. Hence, there was no need for domestic debt restructuring and it was not a condition under the existing extended fund facility or EFF from IMF.

Domestic debt restructuring was necessary because the ad hoc group of ISB holders who accounted for about 50% of the total ISB liabilities had insisted that if Sri Lanka proposed to restructure their lending, a similar restructuring should also be applied to the Government’s domestic creditors too. That is because such international debt restructuring requires the equal treatment of all creditors, known as the comparability principle. Further, without such a domestic debt restructuring program, there was no assurance that the Government will have enough revenue to repay their restructured debt too. Therefore, to satisfy them, the government agreed to adopt a certain domestic debt restructuring program.

Restructuring of debt is a forced application of new terms on debt by getting borrowers to agree to them. However, what was proposed for the domestic debt was not restructuring but a process which the Ministry of Finance called the ‘domestic debt optimisation’ in which the lenders will choose the best option for them. Optimisation in economics means the adoption of the best option to minimise the cost or maximise the profits. In this case, the debt restructuring involves the acceptance of a certain cost by the creditors and therefore, the process was termed debt optimisation implying that it is the creditors who have chosen the given path. In my view, that was a very smart move by the Government. If anybody criticised the activity, it could always turn back and say that it was the creditors who have chosen the path.

Aseni: But was this optimisation applicable to all those who had lent money to the Government in the domestic market?

Sarath: The Government borrows from the domestic market by issuing various types of debt certificates governed by local laws. Hence, it is not identified by the currency but by the law under which the borrowing has been made. There are three types of debt certificates that the Government has issued in the domestic market in this manner. One is the Treasury bills through which the Government borrows for a period of one year or less. Hence, it is essentially a short-term borrowing to meet the government’s liquidity problems. The second is the issue of Treasury bonds and they are issued for borrowing of more than one year. They are medium to long-term borrowing to meet the capital expenditure of the Government. Both these debt certificates are denominated in Sri Lanka rupees.

Then, there is a third type of debt certificates, denominated in US dollars, called Sri Lanka Development Bonds issued under the local laws. There is a special type of lending done by the Central Bank to the Government under the now repealed Monetary Law Act called provisional advances. It is a revolving credit like an overdraft facility in which a credit limit is fixed and when the Government deposits money with the Central Bank, the provisional advances are repaid and when new cheques are written it is used again. The limit has been fixed at 10% of the estimated revenue of the Government as approved in the Appropriation Act by Parliament. For instance, if the estimated revenue is Rs. 1,000 billion, the limit of provisional advances is fixed at Rs. 100 billion at any time.

As at the end of 2022, according to the Government’s borrowing data, the Government had borrowed Rs. 15 trillion or 63% of GDP. Of this, the Central Bank had lent Rs 2.8 trillion that included the provisional advances of Rs. 235 billion. Similarly, commercial banks had lent Rs. 5.7 trillion, and superannuation funds that included the Employees Provident Fund and Employees Trust Fund, Rs. 3.9 trillion. The balance Rs. 2.6 trillion had been lent by others like companies and citizens. The optimisation should have been applied to all these lenders. But they were applied only to the Central Bank and the superannuation funds.

Aseni: You said the money lent by the Central Bank was also subject to the optimisation program. Did the Bank do it voluntarily or was there an element of force by the Government?

Aseni: You said the money lent by the Central Bank was also subject to the optimisation program. Did the Bank do it voluntarily or was there an element of force by the Government?

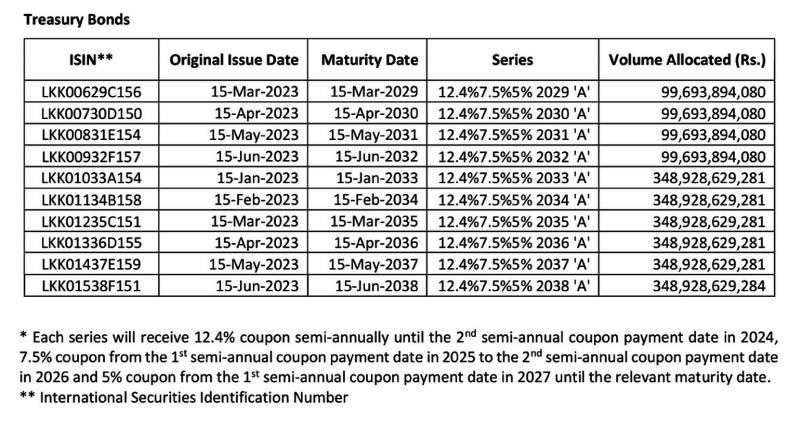

Sarath: It was not a voluntary act by the managing board of the Central Bank called the Monetary Board but rather enforced on it by Parliament when they approved the new Central Bank Act. This was included in the Repeals and Savings section, known as the transitionary provisions of the Act. Accordingly, subsection 2 of the section 129, stipulates that the Central bank after agreeing with the Minister of Finance the outstanding credit to the Government shall convert into negotiable debt instruments. What you mean by the negotiable instrument is that the Central Bank can sell them before the maturity in the secondary market without informing the Treasury which is liable for repayment of same. These are long-term Treasury bonds and the Treasury will pay interest and repay the principal to the bond holder at that time.

The Central Bank did this after it was formed in September 2023. The details are given in the Table I. You will observe that those bonds will mature on a staggered basis from 2029 to 2038. The Central Bank will receive interest at 12.4% in 2023, at 7.5% in 2024 and 2026, and at 5% from 2026 to the maturity date. IMF has advised the Central Bank to sell them in the secondary market as soon as practicable. If the Bank sells them, it will lose the promised interest income on the bonds. Therefore, the Central Bank will lose on two counts. It will have a comfortable income of over Rs. 300 billion in 2024, but, at falling interest rate windows, that will fall drastically in the subsequent periods.

It is estimated that the income will fall to Rs. 124 billion in 2027 and starts falling drastically after the repayments start in 2029. In 2036, it will reach a critical level at which the income maybe insufficient to meet the annual operational expenditure. This will be accelerated if it sells them in the secondary market as advised by IMF. This will create a serious problem for the profitability of the Bank causing a depletion of its capital and needing the taxpayers to provide new capital to it.

Aseni: What about the other lenders to the Government? Was their lending too optimised?

Sarath: Only those superannuation funds which had invested in Government paper had been asked to optimise their lending. But that was done on a false premise and a false threat. The false premise was that the Government maintained that those superannuation funds were subject to an income tax of 14%, while all other financial institutions were subject to an income tax of 30%. There, the wrong premise was that the tax base of the superannuation funds was that they had to pay on the gross income minus administration expenditure and depreciation of fixed assets. That was a minor segment of the total expenditure of those funds, accounting for about 1% of the gross income. Therefore, the superannuation funds paid an income tax of 14% on about 99% of the gross income.

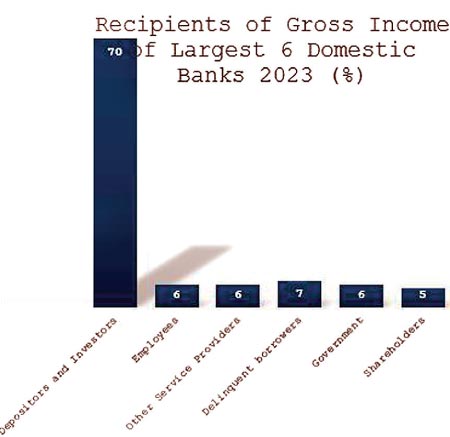

The other financial institutions paid 30% on their net income after deducting the administration expenses, depreciation, bad debt and most importantly the interest paid to the suppliers of the funds, namely, the depositors and the debenture holders. According to the financial reports of the commercial banks for the year 2023, the total of such expenditure amounted to some 90% of the gross income. Hence, these institutions paid a 30% on about 10% of the gross income. Graph I shows the gross revenue distribution of the largest 6 domestic banks in 2023, according to published data by these banks.

You will see the difference now. When superannuation funds paid about Rs. 14 per Rs. 100 of gross income, commercial banks paid only Rs. 3 per Rs. 100 of gross income. Hence, the threat on superannuation funds was based on wrong premise.

Aseni: Why doesn’t the inland revenue exclude the interest paid to members of superannuation funds when the taxable income is calculated?

Sarath: Superannuation funds are owned by members and therefore, any interest paid to the members is considered as profit distribution. Such profit distribution is not considered as an expenditure incurred in earning the income of these funds. Therefore, the tax authorities do not allow these funds to deduct such interest payments to calculate their taxable income. In the case of banks, interest is paid to the suppliers of funds and therefore, they represent an expenditure incurred in earning that income. This difference was ignored by the Government when making the threat that unless they agree to the offered debt optimisation, their income tax rate is increased to 30%. If that had happened, superannuation funds would have paid an income tax of about Rs. 30 per Rs. 100 of gross income, whereas banks would have paid, according to the data for 2023, only Rs. 3 per Rs. 100 of gross income. That would have been very unfair.

Aseni: But EPF, the largest superannuation fund, is reported to have paid 13% to its members in 2023, up by 4 percentage points from its rate of interest of 9% paid in 2022. If the debt optimisation has resulted in a loss, how could it pay such a high interest rate?

Sarath: We cannot comment on that since neither EPF, nor the Central Bank has released the calculation of the interest rate even after six months of declaring that interest rate. The Central Bank has not made the needed disclosure here. This is contrary to Central Bank’s stipulations to financial institutions under its supervision where the latter is required to make full disclosure to stakeholders. The longer the Bank keeps mum on the sources of funds for awarding the high interest rate in 2023, the higher the speculation that there was some accounting window dressing like the use of internal reserves to declare this high interest rate as it had done earlier in 2012. In my view, it is important for the Central Bank to put this uncertainty to an end as early as possible.

(The writer, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected].)