Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday, 3 February 2025 03:13 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The Central Bank should conduct inflation targeting not in isolation but with the approval of the Government

Price stability, main objective of CB

Price stability, main objective of CB

Under the new Central Bank of Sri Lanka Act, abbreviated as CBA, the Central Bank should use inflation targeting as its monetary policy framework.1 Inflation targeting is the operational mechanism of the Central Bank which is mandated to attain and maintain price stability as its main objective and the maintenance of financial system stability as the other objective. Accordingly, price stability preponderates over the system stability. However, these two objectives are interconnected, and the achievement of either one is needed for the other. Consequently, the Bank should tame the public’s high inflation expectations and thereby contribute to the financial system stability too.

Inflation target agreed with Government

The Central Bank should conduct inflation targeting not in isolation but with the approval of the Government. Accordingly, a monetary policy framework agreement, abbreviated as MPFA, should be signed with the Minister of Finance announcing the inflation target in the next period. This was signed on 3 October 2023 between Ranil Wickremesinghe as Finance Minister and P. Nandalal Weerasinghe as Governor of the Central Bank and published as an extraordinary gazette of the Government.2 MPFA has stipulated that the Central Bank ‘shall aim to maintain the simple average of the quarterly headline inflation’ as measured by ‘the Colombo Consumer Price Index’ or CCPI at 5% with a margin of plus or minus 2%’. Therefore, the Central Bank should see to it that the quarterly average of the headline inflation should not exceed 7% at the upper bound or fall below 3% at the lower bound.

|

Central Bank Governor Dr.Nandalal Weerasinghe - Pic by Lasantha Kumara

|

COPF and inflation underperformance report

If the Central Bank fails to maintain the inflation within this boundary, a report should be submitted to Parliament through the Minister of Finance explaining why it has failed and what measures it will take to rectify the same. Since the actual inflation was below the lower bound in the 2nd and 3rd quarters of 2024, the Bank has submitted a report to Parliament, which has been released to the public too, in fulfilment of this requirement.3 The matters have been complicated for the Bank since the inflation had been negative in the fourth quarter of 2024 pushing the country to a state of deflation when its economic growth has been low and stagnant, creating the malady of stagflation. This has been complicated by a deeper deflation at 4% in January 2025 subscribing to the fears that the country has been trapped into a perilous deflation regime. Since this was a matter of national urgency, the report was examined by one of the standing committees of Parliament, namely, Committee on Public Finance or COPF.4

Governor’s solo battle

The arrangement by Parliament for COPF to examine the Central Bank’s inflation deviation report is understandable since the whole Parliament has no time or expertise to do so. The work of the Bank’s technical staff in preparing and presenting the report to COPF is commendable, though a critic has charged that inflation targeting is a myth, the country has been snared in a deflation trap and the Central Bank cannot extricate itself from responsibility for the malady.5 There are some important points made by this critic and, in my view, had they been made available to committee members in advance, they could have subjected the Central Bank’s Monetary Policy Board or MPB members to the strictest scrutiny possible, on behalf of the public, to dig out the real causes for their underperformance.

While these members were strangely silent at the committee’s probing, Governor Weerasinghe who fought a solo battle for nearly two and a half hours did justice to the Bank and its policy stance earning admiration of even an opposition legislator who was not a member of COPF.6 In my view, the Governor was to the point, consistent and confident in what he said and able to maintain the balance in his composition throughout. However, there are certain grey areas that need by highlighted for the benefit of COPF, the public, and even the Central Bank Governing Board members and its technical staff.

Presumed independence of CB

The new Central Bank Act has incorporated this philosophy of central banking to its core provisions. The invisible hand of the minister of finance over the monetary policy making of the central bank has been removed by not making the secretary to the ministry of finance a member of the Governing Board (section 8(2)) or the Monetary Policy Board (section 12). Though the minister of finance still has a hand in recommending the 7 members of the Governing Board, two experts to the Monetary Policy Board and appointing the two Deputy Governors (section 15(8)(a)), they are not direct employees working under him like the Secretary to the Ministry of Finance. Hence, his influence over them is presumed to be diluted. Even if the minister of finance tries to use his invisible hand in directing the policy actions of the central bank, the stature of the people who are appointed to these high posts should prevent him from doing so.

Coordination Council

The secretary to the ministry of finance still has a role to play in the new central bank by being a member of the Coordination Council of the central bank in terms of section 83 of CBA. But the job of that council is to coordinate the work between the ministry of finance and the central bank and not to direct the bank’s policy. Section 5 of CBA has spelt out that the central bank should have financial and administrative autonomy, and it is accountable for it. A missing feature in this autonomy is the absence of policy autonomy which is not covered by the financial autonomy spelt out in the Act.

No to monetary financing

The central bank credit is generated by creating new money and therefore, it is known as ‘monetary financing’. Section 86 of CBA has prohibited the central bank to offer such monetary financing, directly or indirectly, to the Government or any public authority owned by the Government or any other public entity, except State banks for which the bank may lend to overcome their liquidity problems. This is a major departure from the repealed Monetary Law Act or MLA under which the central bank could grant monetary financing by buying Treasury bills from the primary market and accommodate Government’s liquidity problems through an overdraft facility known as ‘provisional advances’.

What this means is that the Government cannot fill its budget deficit by borrowing from the central bank and any development initiative of the Government should be undertaken without the monetary financing support of the central bank. The Central Bank cannot provide loans to commercial banks too under CBA by resorting to monetary financing. Hence, in the new scenario, the Central Bank’s support for economic recovery and growth should not be through money creation but through the maintenance of price stability and financial system stability.

CB’s flexible inflation targeting

Though the statutory provisions are only for inflation targeting (IT), the central bank has announced what it follows is flexible inflation targeting (FIT) moving away from the legal mandate given to it by Parliament.7 By adding this ‘flexible’ feature to IT, the Central Bank has arrogated to itself a space for changing IT, by way of relaxation or tightening the set target, to accommodate the special conditions that might emerge in the economy. The strict inflation targeting seeks to stabilise only the inflation with no regard to what happens in the real economy.8 This is a difficult job because there is a time lag in monetary policy action, transmission of same to the financial sector, and exertion of its impact on the real sector activities.

Time lag to show results

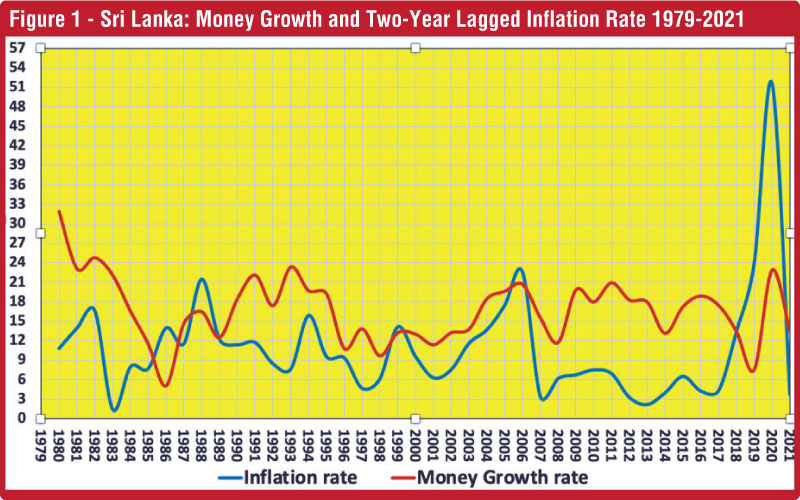

Money and inflation are directly related to each other with a time lag of about 18 to 24 months. Figure 1 establishes this relationship with a time lag of two years for the period from 1979 to 2021, by statistically converting CCPI numbers compiled under varying base years to a single series. Hence, the foremost requirement under FIT is having a forward view of the changes in the economy, government policies, global outlook and take instant remedial measures at least one year in advance. In other words, the Bank should drive the vehicle by looking through the front windscreen and not by constantly looking at the rearview mirror as it had been doing in the past.

Unusual supply-side inflation?

In the present report submitted by the Bank’s Monetary Policy Board or MPB, the blame for underperformance has been placed on transitory supply side factors which have generated what it has defined as ‘supply side inflation’.9 It seems that the Bank’s MPB, devoid of a forward-looking view, has been caught unaware by events over which it has no control and walked into a perilous ambush. This ambush is so disastrous that the feared deflation has now risen from 1.7% at end 2024 to 4% by end-January 2025.

Activation of supply-induced price changes by supportive monetary policy

What the MPB has erroneously identified as supply-side inflation is the reduction in the prices of key commodities in the CCPI basket such as fuel, cooking gas, and the decline in the prices of imported goods due to the appreciation of the exchange rate. In the conduct of monetary policy, which is known as demand management, there is no such thing as supply-side inflation. A general supply shock – a drastic reduction or unexpected increase in the Gross Domestic Product or GDP creating an output gap or an output surplus – will increase or reduce the general price level. But this is only one-time price increase and for it to lead to inflation or deflation, the Central Bank should adopt a counter monetary policy package.

For instance, if there is inflation, the Central Bank should neutralise it by tightening its monetary policy. If there is deflation due to unexpected increase in the output, the Central Bank should take measures to increase the total demand in the economy – known as the Aggregate Demand or AD – by relaxing its monetary policy. The present indications in the economy are that there is no such output surplus in the country warranting a deep deflation of prices. Hence, the reasons have been the drastic curtailment of AD through its disinflation policy package implemented from mid 2022.

Administering inadequate dosage to patient

When the signs have shown that disinflation is occurring too rapidly, the Bank should have applied brakes and reversed its tough monetary policy stance. The Bank did this but not in sufficient volume. As a result, the patient has been given a lower dosage of the medicine than the required one. But in this case, MPB is crippled because it has no expertise to see the emerging destabiliser sufficiently in advance. Since the current monetary policy action takes 1-2 years to show results in the economy, today’s destabiliser should have been neutralised at least one year ago.

What this means is that under inflation targeting, MPB should be constantly in alert for unwarranted developments that might derail its set targets for inflation. Therefore, it is important for MPB that it should drive the vehicle by looking through the front windscreen to install an advanced radar facility to correctly identify the emerging developments-desirable or undesirable-and take timely corrective measures.

Target of 5%: Good for a beginner

The Bank has also been blamed for setting a high inflation target at 5%, in contrast to 2-3% in other inflation targeting countries, and allowing a leeway of operation up to 7% at the top and go below to 3% as the minimum. This was raised at the COPF probing but Governor Weerasinghe’s response was not sufficiently detailed to the allay fears of suspecting members. In my view, there is a justification for the Bank to set a high inflation target initially. The Bank has moved to a new monetary policy framework, and it is still in the learning stage. Hence, it is desirable to start with a high target at first and reduce it gradually when it has got sufficient experience in its new exercise.

Sri Lanka: A high inflation country

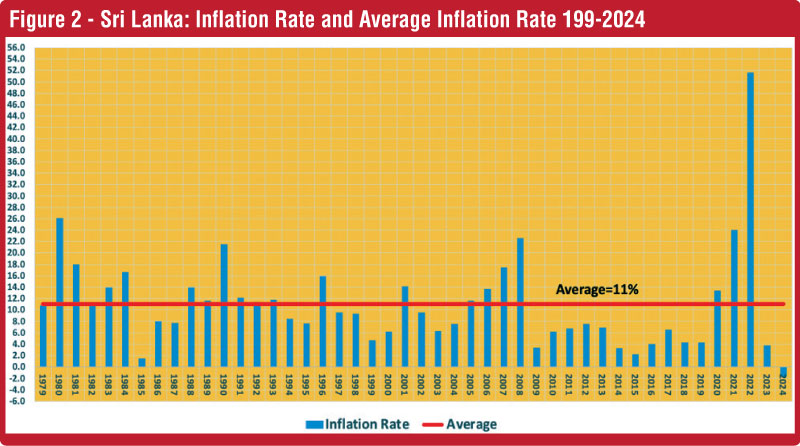

Also, Sri Lanka has been a high inflation country historically. As Figure 2 shows, during 1979 to 2024 during which the country’s inflation was free from Government’s repressions, the average inflation rate has been at 11% per annum. Therefore, to reduce the inflation rate to a single digit level is a gigantic task. As a result, it is always prudent to start with the mid-point in the single digit level as the country’s inflation targeting. But now it seems that the Bank has overkilled its target driving the economy to a state of stagflation. The Bank is confident that the present deflation is technical and transitory and will correct itself by the middle of the year. But the indications are that the output is not rising at the desired level to push the economy out of the current stagflation. There is a statistics-related deficiency also as revealed in the estimation of the paddy production.10

A trial-and-error strategy

Thus, MPB is crippled not only by the long-time lag for monetary policy to take effect but also by having to rely on unreliable output data. This makes it more difficult for MPB to drive the vehicle by looking through the front windscreen. In my view, it takes time for the country to resolve this issue and in the meantime, MPB should adopt a trial-and-error strategy to attain its inflation targeting goals.

Footnotes:

1Part IV of CBA.

2No 2352/20 of 5 October 2023

3Available at https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/sites/default/files/cbslweb_documents/monetary_policy/report_on_deviation_of_inflation_target_Q2_and_Q3_2024_e.pdf

4Live proceedings available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D5v0mMxqGH0

5See the critique in Sinhala by P Samarasiri at 6https://sinhala.lankanewsweb.net/01/30/150935/

6https://economynext.com/sri-lanka-central-bank-exceptionally-great-in-achieving-deflation-legislator-201933/

7https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/en/monetary-policy/about-monetary-policy

8Svensson, Lars E.O, 2009, Flexible inflation targeting: Lessons from financial crisis, available at: https://www.bis.org/review/r090923d.pdf

9Page 2 of the report.

10https://economynext.com/sri-lanka-rice-crisis-due-to-wrong-government-data-minister-201042/

(The writer, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected].)