Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Monday, 30 September 2024 00:22 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The other side of the tea raj

The other side of the tea raj

When the Britishers introduced tea as an export crop to old Ceylon in mid 19th century, it was a game changer. It transformed the traditional subsistence agricultural economy that prevailed to a modern plantation economy seeking to satisfy the demand for the new beverage called tea spreading like a pandemic across Europe and Americas. Initially, it was a beverage of the rich and the aristocrats. A pound of tea was sold, according to advertisements that were inserted in papers, for 25 Sterling Pounds. This exclusive product was made inclusive by ingenious marketing strategies adopted by tea traders like presenting it as a brain tonic.

But when the demand went up, the production too should be stepped up. Since Sri Lanka’s local population was unwilling to work in plantations, the planters had to bring in indentured labour from South India. These men and women who spoke Tamil were a stateless lot not belonging either to India or to Sri Lanka. They were confined to residences known as ‘lines’ where in a room of about 10 feet by 15 feet, about five or six members of a family were packed like sardines in a can. Sri Lanka’s villagers were also poor but these Tamil labourers in plantations were poorer with no facilities for education or social mobility. By any standard, they were in abject poverty.

Mission of PEN International

One of the distinguishing features of Homo sapiens is that they are inclined to artistic expressions no matter whether they live in a cave or in a modern city. Likewise, these Tamil labourers in Sri Lanka’s plantations have taken time to pen poems in Tamil to express their feelings of day-to-day hardships or aesthetic cum religious wishes. These creative works would have gone unnoticed by the rest of us in society if not for the Sri Lanka branch of PEN International, an outfit for writers to express their views without fear or favour.

PEN International which has existed since 1921 says that the objective of its advocacy is for writers to express their views: “Every day, countless writers are detained, harassed, persecuted, or even killed for the practice of their profession. We will not let their voices be silenced. We raise awareness of their cases, campaign against abuses and lobby governments for their release.”

PEN International which has existed since 1921 says that the objective of its advocacy is for writers to express their views: “Every day, countless writers are detained, harassed, persecuted, or even killed for the practice of their profession. We will not let their voices be silenced. We raise awareness of their cases, campaign against abuses and lobby governments for their release.”

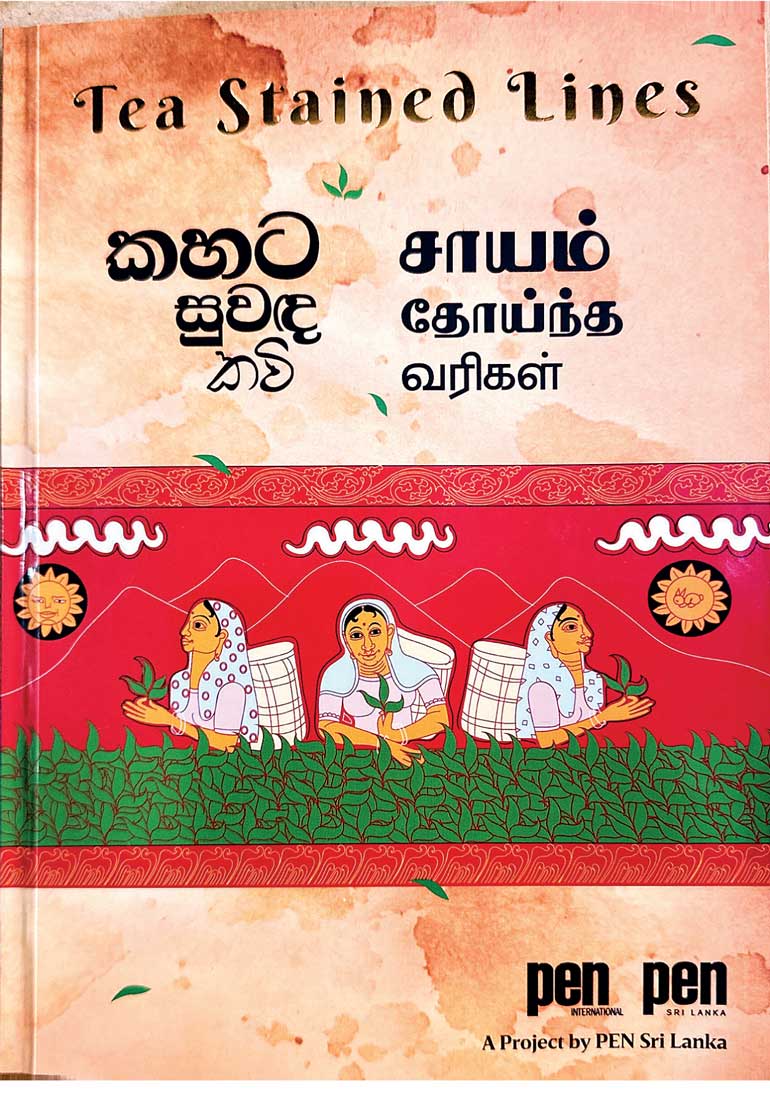

But the present book released by PEN Sri Lanka by laboriously translating the pieces of poetry, originally in Tamil, by these workers into English and Sinhala is a promotional work aiming at building a cultural bond between them and the rest of us in contemporary Sri Lankan society. The book is titled ‘Tea-Stained Lines’ referring to the line rooms in which they are living and, because of their work involving the cultivation, plucking, and manufacturing tea, their bodies and living quarters are also stained by its strong liquors. The mind soothing aroma of fresh tea that you smell when you pass by a tea factory can also be whiffed from the bodies of these social outcasts in Sri Lanka.

It is an anthology of hill-country Tamil poems with translations into English and Sinhala. It is a creditable work and for the first time, Sinhala and English readers could understand that there are in those hills cramped into line rooms, people who are like them with feelings and ability to express those feelings using poetic means.

An extraordinary anthology of poems

The anthology opens with a tribute to one of the leading up-country Tamil poets, C.V. Velupillai who has penned a poem about the drudgery of the tea pluckers from morning to night for seven days a week and for 365 days a year. Titled Tea Pluckers, he has presented to us in poetic language how their bronze bodies move from early in the morning to night from valley to valley among the tea bushes carrying various implements used for weeding, fertilising, pruning, and tending to the tea bushes. He ends the poem: “Eight hours in a day, Seven times in a week, Thus their life blood flows, To fashion this land, A paradise for some”.

So, the tea that we drink enjoying the aroma, tasting the distinguished liquor, and stimulating the dormant senses comes from the sweat and blood of these people who are basically anonymous and unknown. But that is the nature of our perceptions. We see only what can be seen within our eyesight and not beyond. And we do not care. Velupillai has brought this stark reality to us pricking our hearts to a sudden awakening.

Twenty budding poets in a single place

Twenty budding poets in a single place

That is not all. There are 20 more such pieces of poetry. The anthology reveals the addresses and contact numbers of poets but not their background. Therefore, we do not know under what circumstance and difficulties they have chosen the language of poetry to reveal their innermost feelings. But that is not an impediment for readers to appreciate the poems and enjoy them.

All these poems are extremely creative works in my view. But due to space limitations, I will analyse only a few important ones. Readers are advised to have access to this volume and enjoy all the poems which have been penned by a people who have been suffering immensely in their day-to-day life ever since they had landed in this amicable island.

Failure of divinities

Malliyappusandhi Thilakar, one of the editors of the volume, has written a long poem appealing to various female divinities in Hindu religion to descend at least once to resolve the grave problems faced by innocent up-country Tamils. The plea has gone in general to Divine Mother and more specifically to Ambiga, Dhurgha, Kali, Shakthi, Maary or Mary, and Parashakthi, leading feminine divinities in Hindu religion. A separate issue faced by contemporary up-country Tamils is brought to the notice of each of these divinities. Divine Mother is coaxed to appear at least once to satisfy the innocent people yearning her presence with hope. Ambiga to provide nothing for these people but thatching sheets to cover her temple roof, Dhurgha to provide some cement to build the steps to the temple, Kali to see the temple festivities financed out of the meagre donations made by them in her name, Shakthi to take the sufferings out of them, Maary to protect them, and Parashakthi to provide them with land.

He ends the poem by announcing that it would be frustrating to tell them that you would not come. Hence, the appeal is to come at least once and help these innocent people. Thilakar’s message here is very clear. In every society the innocent people who have no other hope except the intervention of the divinities are being exploited by smart people by promising various boons which are never delivered. Hence, it is appropriate if these divinities appear in this world at least once to tell them the truth.

He ends the poem by announcing that it would be frustrating to tell them that you would not come. Hence, the appeal is to come at least once and help these innocent people. Thilakar’s message here is very clear. In every society the innocent people who have no other hope except the intervention of the divinities are being exploited by smart people by promising various boons which are never delivered. Hence, it is appropriate if these divinities appear in this world at least once to tell them the truth.

Life in line rooms

Su Thavachelvam’s piece titled ‘That Day Is Not Far Off’ is an attempt at bringing to our notice the sufferings of these people working in these plantations when we, who might fight for their rights, do so without a true feeling about them. He asks aloud: “Do you know the speed of the pulse in my people?” and “Can you feel the amplitude of their emotions?” and “Does your rusted brain know the vision they behold about these mountains?” As I have personally experienced, the life they live in those line rooms, derogatorily called ‘Laima’ in Sinhala, has been the worst of the human experiences. No one should be condemned to have this life. Therefore, Thavachelvam asks as: “Have you seen how they live suffocated by the smell of the urine that comes from the end of the Laima?” That is only a modest description. The pit latrines are emitting an odour that cannot be borne by even an animal let alone a human. That is why many take alcohol or smote beedis before they go to the toilet. Over time, they get addicted to this sinful practice.

Statelessness or enemy close by

Statelessness or enemy close by

S.P. Balamurugan has drawn our attention to the agony of the statelessness of these up-country Tamils. In his poem titled ‘Uncopied Documents’, he has said that all those living in line rooms in plantations in the up-country are without proper identity documents or documents relating to their origin. Hence, he says: “No records of our existence linger here, no will there be in the future, so let’s breathe life now, into our dreams”. So, when a man is destitute and helpless, there is no other way to seek solation except dreaming. That is because as Balamurugan says the next step without proper papers is a mystery. Hence, he resolves: “Let’s uncover our own identity, and innovate true documents”. This statelessness is a perennial problem faced by up-country Tamils since they were disfranchised in 1950 by the Sinhalese led government of D.S. Senanayake. Since then, neither their leaders nor successive governments have made any attempt at finding a solution.

Betrayal by unions

According to Nalliah Chandrasegaran, up-country Tamils have been betrayed not only by the hostile society but by their own unions. In a piece of poetry titled ‘Collective Agreement’, he has said boldly that “To this land and to tea, we are bound by blood. We who know no joy but pain, our kin, robbed of contentment, were betrayed by the Unions.” The irony is that these Tamil workers are suffering to the hilt and need sympathetic and empathetic attention of unions. Yet, the unions use them as stooges to gain their happy living and the workers raise flags and cry out slogans hailing unions and condemning unseen enemies just for a packet of rice that costs only Rs. 100. On the other side of the coin, these poor Tamils must pay bribes to get identity cards or birth certificates. Yet nothing has been delivered and they remain squandered.

He boldly states: “Will the breeze of freedom ever bring us happiness? Even, once, in heaven? Or will a collective agreement barricade our path, even then?” This is a serious indictment against unions which proclaim to be their saviours. Then, how to save you from the saviour is the biggest issue that you have. The collective agreements have blocked their move forward. The question openly raised here is that those collective agreements which unions sign with employers will block their salvation even after death. This is a good representation of the polarisation of members from union leaders. It is an instance where the enemy comes from within rather than from outside. The fearless poet has raised that issue.

A father’s sacrifice

S. Rathnajothi has raised another aspect of the suffering of these Tamils. Wearing a sarong and a banian and walking bare foot, they seem to be ordinary mortals to outsiders. But they are extraordinary in their behaviour and practices. How? Explains Rathnajothi from the point of a son: “How many days were you in hunger, taking comfort in the sight of your children feeding? No slippers for your feet, yet to provide us with shoes, you carried our weight, worried our feet might get soiled.” It is only an extraordinary man who could endure such pain. So, the wish of the son is to become a son of this extraordinary man throughout this Samsara, the cycle of birth and rebirth which is a part of the belief system in Hindu religion.

S. Rathnajothi has raised another aspect of the suffering of these Tamils. Wearing a sarong and a banian and walking bare foot, they seem to be ordinary mortals to outsiders. But they are extraordinary in their behaviour and practices. How? Explains Rathnajothi from the point of a son: “How many days were you in hunger, taking comfort in the sight of your children feeding? No slippers for your feet, yet to provide us with shoes, you carried our weight, worried our feet might get soiled.” It is only an extraordinary man who could endure such pain. So, the wish of the son is to become a son of this extraordinary man throughout this Samsara, the cycle of birth and rebirth which is a part of the belief system in Hindu religion.

Read this anthology

Because of the space limitation, I have presented only a few of the poems in detail here. But there are others in this anthology whose work by no means is less important. The editors have very carefully selected the poems, edited them suitably, and then translated into English and Sinhala for those outside this community to enjoy. Therefore, the work done by PEN Sri Lanka is creditable. In this literary month in which books are adored by many, I recommend to all readers, Tamil, English, and Sinhala, to have a copy of this anthology and enjoy.

(The writer, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected].)