Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Tuesday, 4 February 2025 01:04 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

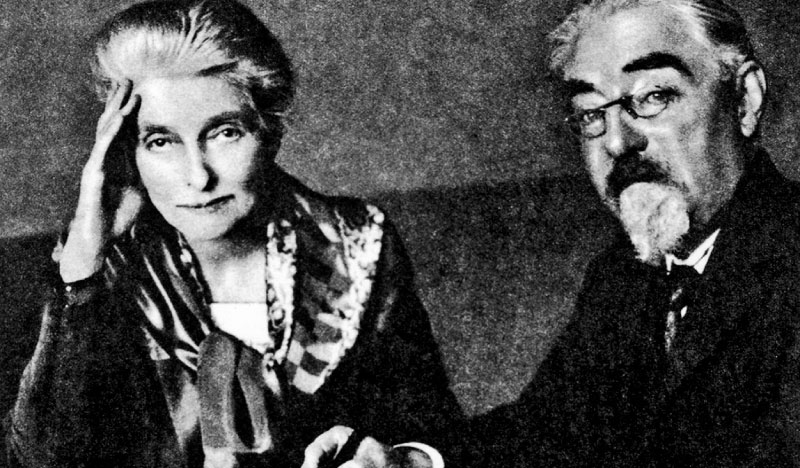

Beatrice and Sidney Webb

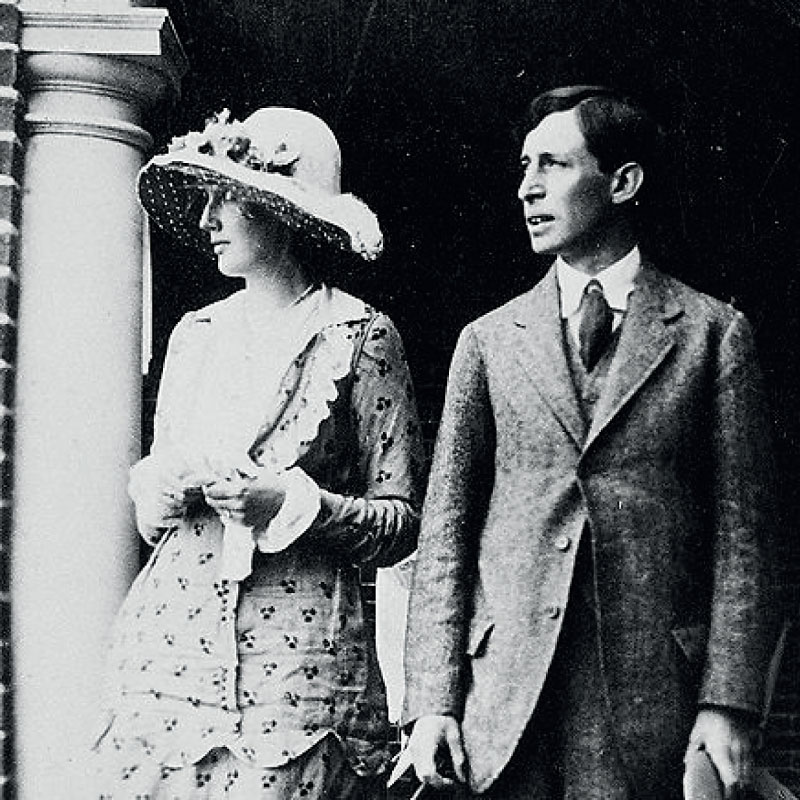

Virginia and Leonard Woolf

|

On the 77th anniversary of Sri Lanka’s independence from colonial rule following foreign domination of some four and a half centuries, the focus may well be on liberty from oppression or tyranny, and sundry freedoms in the sociopolitical and economic spheres.

On the 77th anniversary of Sri Lanka’s independence from colonial rule following foreign domination of some four and a half centuries, the focus may well be on liberty from oppression or tyranny, and sundry freedoms in the sociopolitical and economic spheres.

But the right to chart one’s course as a sovereign nation state had a deeper anchorage in the case of the once model crown colony of Ceylon. And the granting of suffrage – in stages at first, and then universally for adults – played a significant role in the emergence and development of our country’s polity as it is today.

In the second part of an article on some of the elements leading up to the strategic grafting of universal adult franchise onto the people of colonial Ceylon following the Donoughmore reforms of 1931, we look at how the successive foundations for eventual total independence were laid.

That is a tale of gift, grant and a gentler-than-elsewhere raft of agitations against a long-lasting empire on its last legs.

The previous piece approached the historical developments from the perspective of state and legislative councils, as well as the imperial underpinnings and native stirrings that brought political and constitutional matters to a head.

Today we conclude the tale by beginning at the point at which a commission from Great Britain arrived on Ceylon’s fair shores with a view to doing something drastic about a shining gem in the imperial crown.

[Continued from a previous issue...]

|

Dr. Thomas Drummond-Shiels

|

To dismantle an empire

A Donoughmore Commissioner, Dr. Thomas Drummond-Shiels, who had been appointed by the then newly-appointed Secretary of the State for the Colonies, Sidney Webb (who had been made a peer – Lord Passfield – by the Labour Government of the time), was to play “a key part” (Jane Russell, Universal Franchise for Ceylon in 1931: the Complexities of Governance and Policy, 18 July 2021) in granting Ceylon universal suffrage.

A Marxist and an anti-imperialist, Drummond-Shiels was a close ideological associate of Webb – a neo-Marxist and an admirer of the Soviet Union – who would definitely become “the intellectual driving force” (Russell, 2021) behind the Donoughmore Commission.

Privately, he had been instructed by the new Colonial Secretary to use the opportunity presented by the Commission, which had been tasked to develop a constitutional settlement for British Ceylon, to find some constitutional process (an institutional mechanism) which would serve as a precedent and allow the government in London – Labour in coalition with Liberals for the first time – to dispose of their imperial possessions in a way that was both politically practicable and ethical, but also in as timely a manner as possible.

Ceylon was therefore chosen to be the laboratory for an experiment in “not-quite but almost self-government” (Russell, 2021) which would eventually lead not to outright independence (as eventuated in 1972) but to Domininon Status (as was granted in 1948) – the same status accorded within the Empire to Australia, New Zealand, Canada and South Africa.

It seems that Ceylon was considered to be perfect for this attempt at dismantling Empire. In fact, it was to be an experiment in “7/10ths self-government” (Russell, 2021) because three British officials would be Ministers of Finance, Foreign Affairs and Internal Security, while all other ministerial posts would be given to locals elected to the State Council.

Another reason why the Leftists in the neo-Marxist-led Colonial Office thought Ceylon was so well-suited for democratic development at the time was that its relatively privileged status of being a Crown Colony insulated it from the influence of India and Ceylon’s other South Asian and even South-East Asian neighbours (Russell, 2021).

India was administered by the India Office while Ceylon was run by the Colonial Office; so in the democratisation of the latter, the former had no say. This effectively sealed the fate of the Indian Tamil population who tended the Crown Colony’s lucrative highland plantations. Because when the Donoughmore Commissioners left, these ‘upcountry Tamils’ were disenfranchised as India could not claim them and Ceylon would not name them as their own (Russell, 2021).

It was not only the reality of these upcountry Tamils being disenfranchised immediately but a feeling that the Ceylonese Tamils had that the Donoughmore reforms would be detrimental to their own interests that dominated the native political discourse at the time (Russell, 2021).

Despite minority misgivings and active boycotting, on 15 April 1931, the Order in Council to introduce the new State Council was published. One former Governor of Ceylon described the new Constitution as one “conceived in a delirium and born at a stage of coma” (K. T. Rajasingham, Sri Lanka: The Untold Story, Asia Times Online, 22 September 2001).

Maelstrom of reforms

So how and why did the Donoughmore reforms result in such a maelstrom? And was it as delirious and stillborn as the sentiment above suggests? Or were there other forces at play that only a closer look at personages as much as principles and policies reveal a deeper vein of intentionality and almost inevitability?

In reality, a man and a movement were more than instrumental in making the outcome of the Donoughmore Commission a foregone conclusion because of the machinations behind the scenes.

To British Leftist eyes, Ceylon – wealthy from its commodities trade; culturally developed thanks to a 2,500-year-old Buddhist civilisation; with a low population density and yet enjoying high literacy; lacking in major urban centres dominated by a plutocratic class where revolution may be seeded; possessing an English-educated elite; a society where women had property and marriage rights equal to men; the beginnings of a trade union movement; possessed of a recognisable native political party, the Ceylon National Congress (CNC); and where the white (mostly British partly European) plantation-owning community was small – all of which as argued by Russell, as quoted on Thuppahi’s Blog (https://thuppahis.com/2021/07/18/universal-franchise-for-ceylon-in-1931-the-complexities-of-governance-and-policy/) – was a recognisably ‘Westernised’ country ripe for becoming a fully fledged democracy.

Yet, as noted by the same observer, it also had all the other complexities associated with Indo-Asian political cultures: caste-based, religious, racial and language differences; diverse climatic zones; vestiges of tribal peoples and customs.

In short, per Russell, “Ceylon seemed a society that could be used as a model for future constitutional settlements; not just in the other Crown Colonies, but for all Imperial possessions, including the crown jewel of the Empire: India” (Thuppahi’s Blog).

The Donoughmore Commission was therefore sent to Ceylon in 1928 as the harbinger of Imperial divestment: “Its job was to write the template for the leaving card of British Empire.” (Russell, 2021, as quoted on Thuppahi’s Blog).

Drummond-Shiels, cited above, was a member of that “prestigious political institution” (Russell, 2021) the London County Council (LCC); and together with Sidney Webb (later Lord Passfield) and his wife Beatrice, as well as celebrated Victorian novelist Virginia Woolf and her husband (the former civil servant in Ceylon and a novelist Government Agent in his own right Leonard Woolf) became “the Left-wing brains trust” (ibid.) who “sketched out a plan to introduce London’s electoral and governmental system into British Ceylon” (ibid).

This, they rationalised, would best take the shape and form of granting Ceylon universal franchise, alongside introducing an Executive System of governance. This they hoped would produce stable self-government in the model Crown Colony, and also silence their political opponents such as Sir Winston Churchill, Neville Chamberlain and other Conservatives. Together with their Tory peers in banking, finance and the media (like Lord Rothermere and fellow Right-wing press barons) who argued that “peoples of non-white British colonies were incapable of running their own affairs” (Russell, 2021).

Ironically, universal franchise was not something demanded by anyone in the Sinhalese, Tamil or Muslim communities at the time. Even the more vociferous champions of a better deal at self-representation for the Ceylonese at the time, such as A. E. Goonesinghe and George E. de Silva, “argued for a franchise of males over the age of 21, resident in Ceylon, who had at least a primary education, and had a sustainable means of income” (Russell, 2021). As she also notes: “What they got was beyond their wildest dreams – and indeed, was the stuff of nightmares for all other representatives of Low Country and Kandyan Sinhalese, Ceylon Tamil, Muslim and Burgher communities consulted by the Commission.”

The same commentator observes that another irony was that the word ‘grant’ suggests that the people of Ceylon at the time were demanding and lobbying for universal franchise in the late 1920s when nothing could be further from the facts. And what most of the political and commercial elite of the island wanted and asked for when the Donoughmore Commission alighted on the colony’s shores was a slight extension of the existing, very proscriptive, male franchise.

What they got in universal franchise destabilised the island’s political culture immediately. It led to the Jaffna boycott, a pan-Sinhala Board of Ministers, and the final rejection of all communities of the Executive Committee System, in favour of the Westminster model of parliamentary government, which proved even more unsuitable and has now been replaced by a mixed-French model.

|

Republican trajectory

Another putative outcome of the Donoughmore Constitution was that Ceylon continued on its trajectory to become a Dominion and then a Republic rather than – as may have happened if one imperial department had overseen India and Ceylon rather than two – being annexed by India “as part of a gift from one Empire to another” (Russell, 2021).

And so, universal franchise was grafted on Ceylon in 1931. In the minds of its authors, it was a necessary act – done for the greater good of the world. It was done to rid the world of the racial and political injustice of Empire while introducing democratic values in governance in former imperial entities and as an exemplar for modern governance throughout the globe (Russell, 2021).

Overall, one might argue, as Russell does, that it has worked:

“India is still the largest functioning democracy in the world. Pakistan and Bangladesh swing between democracy and army takeovers. Myanmar is trying to get democracy back after decades of military rule. Ghana, and to a lesser extent Nigeria, Zambia and Kenya are functioning democracies in Africa. Hong Kong is a special case; but Jamaica and other islands of the ex-British Caribbean have stuck with democratic norms. South Africa, after decades, overturned minority race-government in favour of majority rule.”

There are however “dreadful failures”, as once again Russell expresses it:

“Nigeria and Uganda have been through terrible periods of bloodletting. The Lebanon sadly, and through no fault of its own, is a basket-case; and the Israel-Palestine issue is still a running sore on the world’s body politic. But Ceylon’s contribution to world history in taking on universal franchise, unasked and probably prematurely, yet making it work so well for so long, has resulted in perhaps a fairer and more equal world, than otherwise might have been the case.”

Other commentators (cf. Nira Wickramasinghe, ‘Colonial governmentality and the political thinking through “1931” in the Crown Colony of Ceylon/Sri Lanka’, Socio: Open Edition Journals 5 (2015), pp. 99-114) would agree that the Donoughmore Commission on constitutional reform brought about an unprecedented form of self-government to the Crown Colony of Ceylon in the 1930s.

The committee headed by Lord Donoughmore was sent to Ceylon in 1927 by the British Government to examine the existing constitution and to make recommendations for its revision. The Commission recommended a radical extension of the franchise until now limited to a tiny portion of educated Sinhalese and submitted its report to an unusual Secretary of State to the colonies, (Sydney Webb, Lord Passfield), who was also the joint founder of the Fabian Socialist Society and the London School of Economics (LSE).

He accepted all the Commission’s proposals and even went a little further, which entailed universal adult suffrage for the Ceylonese, whereby literacy and property qualifications that had been in force were abolished, and residency became the criterion of civic rights.

Experimental ethics

Thus, in 1931, 17 years before the country became independent, conventional history tells us that the then Ceylon became the first Asian country to be bestowed with universal suffrage in an interesting experiment in colonial self-governance. Wrongly described, according to Wickramasinghe, as “a major departure in British colonial administration” – since similar moves towards majority rule were occurring in other places of the Empire such as Palestine – the event is generally read as a ‘hurrah moment’, a pioneering effort towards the extension of the public sphere (Wickramasinghe, ‘Colonial governmentality and the political thinking through “1931”, 2015).

Indeed the number of eligible voters jumped from 205,000 in 1924 to more than 1.5 million in 1931. The liberal story of the extension of the vote and Sri Lankan exceptionalism needs to be measured against the way the granting of citizenship actually entered people’s lives … this includes – and especially encompasses – women’s lives in a surface, diffuse and impermanent way, as Wickramasinghe concludes.

One might well reach a conclusion that the granting of universal suffrage to the people of Ceylon was an event that looks different when it is perceived through different lenses.

From above, it appears to be the unsolicited gift of a king and his government. But from below, there is the agency of a polyglot and ethnically diverse people agitating against each other to drive hard bargains to extract a grant from their colonial masters.

From a via media point of view, and particular angle focusing on personal and political agendas, it looks to be the major grafting work of a small group of Liberals and Labour Party officials of government who were in the right place at the time.

One is grateful the gift, or grant, or grafting on, took place at all. One is also gobsmacked that it redounds more to pragmatism than ideal, the last hurrah of an old empire creaking at the seams, and keen to exit the world stage as an imperial power by ‘doing the right thing’, ‘the only thing’.

[Concluded]

Part 1 of this article can be seen at https://www.ft.lk/wijith-dechickera/Gift-grant-and-agitation-against-a-great-empire-in-its-final-days-Part-1/10503-772550

(Editor-at-large of LMD | #freedom #franchise)